Dungeon Room Appendix: Doors, and Locks

Tamás Kisbali commented on my last post on Hallways and suggested I should talk about Doors.

I chuckled to myself and thought "Ha! DOORS. What would I even say about doors?". I think it was the next day that I started to get a twitch in my eye; I do have something to say about doors!

"Doors" and "Locks"

First of all, let me spoil the punchline; it's not so much doors that are interesting as much as "locks", and when I say "doors" and "locks", I'm going to spend less time talking about literal doors and locks and more time talking about.... like.... the metaphor, man. That said, let's take a minute on:

Literal doors

There's a little bit worth saying about actual, physical doors.

While "realism" isn't always the best goal for a game about fantasy adventure, it is a useful place to look for gameable insight. (Especially in a game that relies on so many default assumptions about reality to function.)

First, lets consider doors based on what they're made of:

- Wood. It's pretty breakable. It can burn. It can warp and swell from water damage. It can rot. It could be worth considering what kind of wood the door is made of but that's aesthetic. I suppose some kinds of *special* wood could be flame proof? That sort of thing. (Don't surprise someone with that; you signpost that sort of thing, because that feels bad.)

- Stone. Stone doors have got to be so heavy. But it would take a lot longer to wear away. It can be chiseled or pickaxed.

- Metal.

- Solid. Soooo heavy. Durable. Very durable. Unless they get wet of course; I would think even a stone door would withstand water better. Theoretically it could be melted (at very high temperatures), and it conducts heat and electricity, so that could be fun for incorporating into a strategy or a trap.

- Barred. A really interesting choice, because it's implicitly "transparent". Can be pretty effective nonetheless. Same drawback as a solid metal door.

- Are they super old?

- Old wooden doors will either rot or become petrified. Old metal doors may rust. Old metal locks may rust.

- A particularly old dungeon (especially one that isn't just carved into the rock, though this could theoretically happen in those too I guess) may "settle" over time, resulting in doors becoming completely jammed. I imagine wood doors and metal doors would jam effectively (they can bend and compress a bit) but stone doors seem like they'd ultimately crack and break under those conditions. Jammed doors can't just be opened by pushing on them. It's gonna cost something.

- If the door has metal hinges those are quite likely to rust; that means they're going to take effort to open, and be noisy. At the very least creaky. I sure hope your stone doors have some kind of metal hinge, because otherwise...

- Stone doors have got to be hard to open right? Stone hinges? Really? That sounds hard and loud.

- Disregard all this for fancy secret stone doors like in the movies; I mean come on, it's cool right? Basically if some mechanism opens it all dramatically, it grinds open and you're off to the races. I'm thinking mostly about doors that players are going to try to force open by manual means.

- Are they new?

- A dungeon is a living space; I imagine that sometimes the denizens replace the old doors, or install doors where they weren't before. That means you can handwave newer doors to an extent; though the style of the door is likely to differ.

- Doors aren't "seals".

- In the course of play, I frequently have seen it assumed that if you're on one side of a door, and something else is on the other, that you are more or less "hidden". But that really depends doesn't it? Even my very modern, well built doors at home have space underneath; if they didn't they would be pretty hard to open without dragging across the floor (inefficient, and noisy). And if a wooden door isn't made of a single solid plank of wood, then the older and more warped it is the more likely I think you'd find small seams in the wood. All of that means that if the dungeon is dark and someone is standing on one side of it with a blazing torch... that's going to be pretty obvious to anything waiting on the other side. (Unless they are very distracted, and perhaps have light of their own.) It also means that listening or peeking at doors frankly ought to be relatively easy. (Especially if those on the other side have light!)

Things to think about. Candidly, I'm not sure how many of these ideas will improve your game or ruin it; you know your group better than me, so have at ye!

Now, for the idea that really piqued my interest:

The Metaphor

What is a "Door" really? Basically, it's a permeable barrier between two spaces; one which must be engaged with to be passed. (As opposed to a "Wall", which is something meant to be completely impassable.)

And, what is a "Lock", really? What role does it play in a dungeon setting? Well, that's simple: a lock blocks progress in a certain direction.

"Blocks". Hmmm. Fishy.

See, the whole point of a locked door in a dungeon isn't actually to keep someone out. What player has ever come across a locked door and said "well, pack it up lads! Looks like we're not getting in today!". Of course not! Therefore, the purpose of a lock isn't to keep someone out; it's to challenge them to find a way in.

So too with the metaphorical "lock": any obstacle which is intended to challenge a player before letting them pass. That challenge can take a wide variety of forms, but the basic principle is the same. A lock is a taunting hoop waiting to be jumped through.

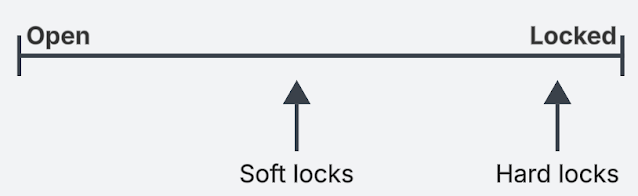

But all locks are not created equal! There are "hard" locks, and there are "soft" locks. In fact, rather than thinking about things as being "locked" or "unlocked", I think it will be more useful to think of this as a spectrum from "open" to "locked".

Open

The left side of the spectrum (the "open" side), represents any situation in which progress is trivial. An empty hallway is "open". A room without anything challening in it is "open". An unlocked, new, well-oiled-at-the-hinges door is "open".

"Open" situations are not strictly-speaking "fun", yet without them the game can become unfun or frustrating or a slog. Generally, I doubt you need to think much about Open scenarios in your prep; they come fairly naturally, and I'd wager you're more likely to have too few Locks, not too many. At the very most, check your work occasionally and ask "is everything Locked? Or is there a little breathing room in here?"

Locked

Locks on the other hand are very worth your consideration.

I alluded to Soft Locks and Hard Locks before. Let's place those on the spectrum.

Hard Locks

This is pretty straight forward: a Hard Lock is when the only way forward is to have a very specific Key. For example, you enter a dungeon to see a towering, thick door of some kind of unknown metal. It's huge, it's heavy, nothing you have can put a scratch on it, and it seems resistant and dampening to all magical influences. But it has an obvious "key hole", though too large for your lockpicks, and in a very peculiar shape--clearly this door has it's own key somewhere, and the only way you're getting through this thing is to find it.

Easy-peasy. A Locked door, and a Key.

Stretch your mind though (that's what we do here right?): can you come up with anything else that fits the same description? Try this: a treasure hoard is guarded by an Ancient Dragon--cunning, powerful, and perceptive. It never sleeps, it cannot be tricked, and it's scales are impenetrable to any kind of harm mundane or magical... except the mystical ancient Sword Of Dragon-Slaying.

The Dragon is a Door, it is Hard Locked, and the Key is the magic sword.

Soft Locks

Now let's compare that to a Soft Lock: a regular dungeon door. See, there's this door, and it's locked!

Well, let's really think about this: how many ways are there to bust this thing open? Surely you could find the key; that's one way. You could also pick the lock in some fashion; there's another. The door is made of wood, so you could probably burn it if you're a little patient, and also it opens into the room you're in, so it has exposed hinges--with the right implement you could probably pull the pins out of the hinges and pull the door right out of it's frame! Heck, you could just bust this thing down with an axe!

But the metaphor: (if you read my recent post on hazards you might see where I'm going with this) consider a lava pit. There's a room with an entrance on the south (where you came in) and one on the north... and there's a lava pit in between. There's no pathways around... Oh well, pack it up lads! Guess we're not getting in today!

Wrong!

This is a Soft Lock! Got some magic? Maybe some kind of a levitation spell? Boom. You're in. What about some sort of powerful freezing spell, or summoning a huge quantity of water? You're in. Special climbing gear? Work your way across the walls or ceiling? You're in! I'll let you come up with other ideas; I think you get the picture.

A note on Keys

Most challenges are Soft Locks, and Soft Locks are goood. But what are Keys? Like, how broad is this category? Well, remember how I described the Hard Lock? You have this Door, and you need something specific to get through it? You can abstract that idea to absurdity: you want to become a Wizard; the only way to become a Wizard is with great study and time. Becoming a Wizard is the Door, it is Locked, the Key is Study and Time.

Har har. Maybe this way lies madness, but before I abandon this railroad to insanity, let me say something substantive: if all it costs you to get through an obstacle is valuable torchlight or perhaps jeopardizing your stealth with light or noise, you can consider those Keys, and the scenario can still qualify as a Soft Lock. It's a spectrum remember; some locks are very Soft, some locks are very Hard, and there's a lot of space in between.

One-Way Doors

An interesting variation on this theme is a One-Way Door. By the terminology I've established, a One-Way Door is any Door who's position on the Open-Locked spectrum is different depending on what side of the door you're on.

This can be a very light contrast (e.g. the methods you used to move in one direction won't work moving in the other, but there's overlap, or a similar quanitity of viable methods), or it can be a stark contrast (e.g. there was no difficulty at all getting in, but it's going to be pretty tough to get back out).

For example, in my Entrances post, I posited a cave entrance that is just a high cliff over a deep pool of water. If you're willing to jump, that cliff is very Open going in; but once you've jumped, it's not at all trivial to get back out again--you're going to need some kind of Key.

Height is an easy go to for a kind of One-Way Door, I've also alluded to a variety of hazards that basically amount to One-Way Doors, and really any trap or challenge that is "disarmed" becomes a kind of One-Way Door (I'm running long as is, so I'm going to remain at the level of theory rather than listing out more ideas for this one)

Putting Locks to use

Ok, so how should you use Locks? Well, let me get one thing out of the way by saying: don't use too many Hard Locks. At least not if you like Tactical Infinity (see, this is just a post about Tactical Infinity in disguise!). That said, I wouldn't say don't use any. Hard Locks are useful, and can be interesting (as long as they don't feel arbitrary), and one could perhaps argue that sometimes they're even necessary.

Plus, it's a spectrum remember? You can totally use Hard-ish Locks that simply have very few keys, to great effect. But use with care. Ask yourself "could this be a Softer Lock?" and "what are the possible Keys to this Lock?"

Soft Locks though, spread those around liberally. Soft Locks are the game.

There are broadly two ways to do this: randomly generate them, or place them with design intent.

If you like the first approach, great! All you need are tables for generating hazards, encounters, and y'know locked doors (the literal ones), etc. You come up with your dungeon room layout (or generate it), then you roll to come up with your "encounters" here and there, and then you're done. This is valid, and the results are often pretty good. I recommend starting with this, and using the second approach to augment your results when you feel the need.

If you like the second approach, then I'm going to mostly point you to the Cyclic Dungeon Generator--where the seed of this paradigm was first planted in my head--that is a golden piece of writing, but I'll summarize and elaborate on it briefly here:

The basic idea is that you build your dungeon out of "cycles" (and then you nest cycles withing cycles, effectively branching off kind of fractally). A "cycle" is more or less a path through the dungeon, particularly one that forms a loop. In other words, from any given starting point A, there are at least two paths to point B, and they either differ aesthetically, or there's some kind of barrier (a Lock) along each path. That could be a short path with a challenge in the way vs. a long time-consuming path, or two paths that both have a Key that needs finding, and so on. It's a great read! I highly recommend it!

Assuming you've read it or you get the gist, let me speak a little to the why of it all: this game is about choices. (Unless the game you're playing is just about monster combat; I'm a fan to a degree, but if that's you, I hope you've realized by now that you're not exactly my core audience.) Therefore, the goal in creating something for players is to present them with choices.

Lock's are all about that, and the placement of Locks is all about adding richness and variety to those choices. A simple Soft Lock, embedded on a linear railroad, is highly gameable all on it's own; it let's players shake the dust off their brain folds and come up with new ideas--and that's rewarding! But an arrangement of Locks of varying Softness/Hardness, combined with a well Jacquaysed space, is arguably what makes Exploration in a dungeon context worthwhile.

Fundamentally, I think that is the difference between feeling like you're on a railroad, and feeling like you have actual freedom: not only can you choose how you approach a problem, but you can choose which problems you want to invest in at all.

Miscellany

Let me voice some disorganized thoughts related to this subject, and we'll call it a day:

- A Wall that you can see through is a Window. (Getting tired of this metaphor yet?) This idea comes up in the Cyclic Dungeon Generator, and Windows are good; they let you foreshadow or tease future content and spur players forward to explore new paths to obtaining the prize. Tactical infinity being what it is, a true Window can be hard to establish, nevertheless transparent Doors are great too, if the Key is particularly expensive.

- Hard Locks create a kind of cognitive dissonance for me at times; depending on the nature of them, I am left wondering: how are the denizens of this space even here if it's shut up tight? If there's a literal locked Boss Door in your dungeon, how do the living things inside survive without the Key? For these reasons, I usually place alternative hidden entrances/exits to the space, just hidden so well from the outside that players aren't likely to find them. That could be a secret door that's more or less invisible from the outside (this is totally legal, and not hard; you hold the spotlight), or just an alternate exit (I consider dungeon entrances to generally be the sort of thing you don't run into by accident--unless they are particularly grand--and combing the foothills for that little secret cave mouth that shortcuts you to the back of the dungeon is either incredibly resource intensive, or incredibly boring, so no worries there--consider alternate entrances to be a reward for player exploration.)

Thanks for reading! Hope it was helpful.

Comments

Post a Comment